General Shoulder Surgery Risks

Surgery is a carefully choreographed process and you are being treated by a sub-specialist shoulder surgeon and a highly experienced team; however, all surgeries inherently carry some risk of complications, such as (all are below 1%). The most common risks include:

- Infection

- Nerve injury

- Bleeding

Specific Shoulder Surgery Risks

Frozen Shoulder

Frozen shoulder occurs when the shoulder joint capsule becomes inflamed, red and scarred – it initially presents with severe pain, then progresses to stiff ness and thaws out over many months

- After routine shoulder surgery the risk of frozen shoulder is 5%. There is nothing you or your surgeon can do to reduce this risk

- This risk is 10% if you have a history of Diabetes or Thyroid disorders.

Frozen shoulder progresses through three phases (which may each last 2-3 months):

PHASE 1 – Painful (even at rest and at night)

PHASE 2 – Stiff (reduction in movement)

PHASE 3 – Thawing out (increase in movement)

Natural history of frozen shoulder

Physiotherapy is not generally helpful in the first TWO PHASES of frozen shoulder. Once your shoulder starts to thaw out then you can work with your therapist within the arc of movement. Outcomes after a frozen shoulder:

- Although it is a nuisance, a frozen shoulder will NOT change your outcome overall after surgery

- In fact, in some cases, it is actually protective of your surgical repair

- Occasionally patients need a second operation to “release” the frozen shoulder key-hole. This surgery is uncommon.

Reoperation and failure of shoulder surgery

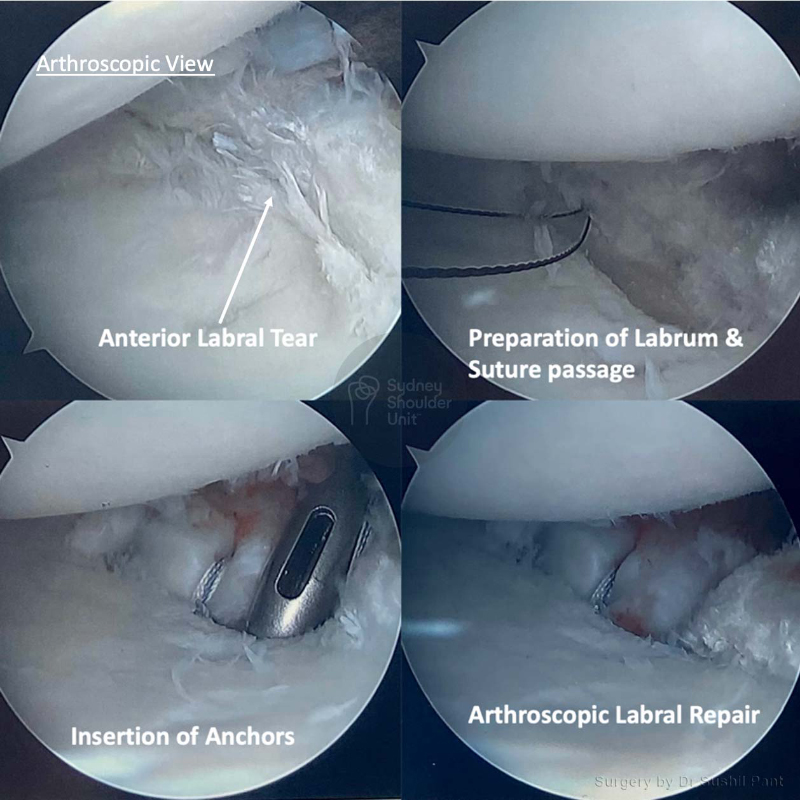

When performing a shoulder reconstruction, your surgeon is using your own tissue to repair what is damaged. The weakest point in the repair is your own tissue. The longer the history of damage and frequency of dislocations/instability prior to surgery, the more likely the tissue quality is poor. There are three areas where your shoulder reconstruction may fail:

- Bone-Anchor interface. The anchors today are very high in quality and usually do not fail; sometimes if your bone is soft (older patients), the anchor may pull out of the bone.

- Anchor-Suture interface. This area is typically very strong and not a source of common failure.

- Suture-Tissue interface. This is the weakest point and the most common reason for failure of surgery (usually due to poor tissue quality)

There are special techniques in tissue management and suture choice to reduce failure rates.