Menu

- About Us

- Shoulders

- Shoulder injuries and conditions

- Acromioclavicular Joint Arthritis

- Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocations (Shoulder separation)

- Biceps Tendonitis

- Biceps Tendon Tear

- Calcific Tendonitis

- Collarbone Fracture

- Frozen Shoulder

- Shoulder Dislocations

- Labral Tears

- Pectoralis Major Rupture

- Proximal Humerus (Shoulder) Fractures

- Rotator Cuff Tears

- Shoulder Impingement

- Shoulder Joint Arthritis

- Shoulder Spur

- SLAP Tears

- Subacromial Bursitis

- Shoulder Surgery

- Acromioclavicular Joint Stabilisation

- Arthroscopic AC Joint Resection

- Arthroscopic (Keyhole) Labral Repair

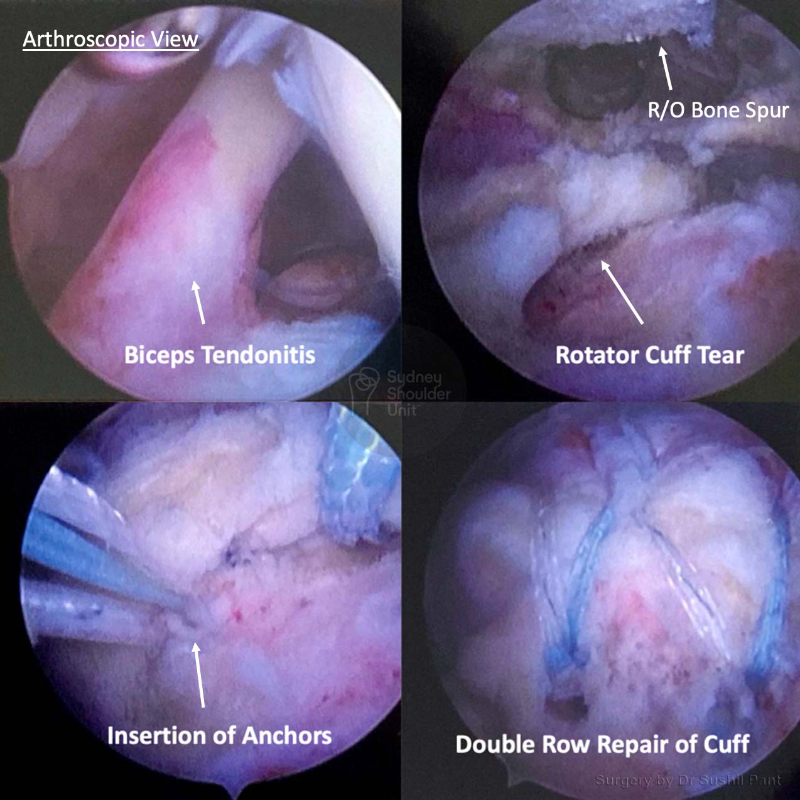

- Arthroscopic (Keyhole) Rotator Cuff Repair

- Arthroscopic SLAP repair

- Biceps Tenodesis

- Broken Collarbone Surgery

- Latarjet Procedure

- Fixation of Proximal Humerus (Shoulder) Fractures

- Subacromial Decompression and Acromioplasty

- Reverse Shoulder Replacement

- Total Shoulder Replacement

- Case studies

- AC Joint Arthritis

- Broken Collarbone – Cycling accident

- Broken Collarbone – Scooter accident

- Shoulder Fracture – Complex Humerus Fracture

- Shoulder Fracture – Displaced Humerus Fracture

- Shoulder Fracture – Scooter accident

- Shoulder Fracture – Gardening

- Shoulder Fracture – Proximal Humerus

- Reverse Shoulder Replacement – Pain

- Reverse Shoulder Replacement – Shoulder Pain

- Rotator Cuff Tear

- Rotator Cuff Repair + Biceps Tenodesis

- Shoulder Dislocation – Latarjet

- Shoulder Dislocation – Instability

- SLAP Tear

- Total Shoulder Replacement

- Shoulder injuries and conditions

- Patient Info

- Articles

- Gallery

- Locations

- Contact